Free Some Space for Weak Monuments

1

Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, the head curators of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, have titled this year’s event Freespace.1We are in for hefty discussions about the concepts of the public sphere, public space, the commons and commonwealth. Once and for all, how does architecture serve the common good?

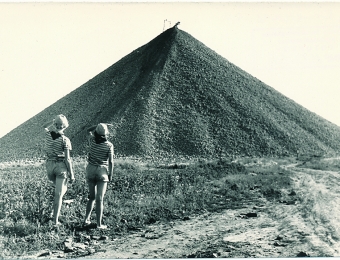

The Estonian national pavilion Weak Monument starts from this eminent question and asks how architecture – or to be more precise, the more mundane built environment – represents the good or the bad (or whatever it happens to represent). We are used to talking about paintings, sculpture and monuments symbolizing ideas such as national identity or depicting certain historical events, but what about simple infrastructure, our daily environment, or – as the curators Laura Linsi, Tadeas Riha and Roland Reemaa put it – weak monuments?

At first sight, the word “monument” seems to be misleading here. In fact it seems a major put-off, as people in various parts of the world have grown tired of the public disturbances which this “genre” seems to cause. This time the goal is to undo the monumentality and instead focus on the weakness. “Weak monuments” means frail streets, feeble buildings, fragile fountains, delicate crossings, shaky squares, worn out tunnels and weedy bridges. The ordinary stuff in the city. Do such indistinct details of architecture as pavement or scaffolding stand for anything specific? Can they act the same way as monuments do (supposedly they firmly represent something)?

Although old-fashioned political monuments are said to be dead, the need to represent, to make public space meaningful has not disappeared. Will the weak monument take over from the strong monument? Are we not already experiencing more and more architecture and infrastructure becoming increasingly “talkative”? What is the language that weak monuments speak? Is it well-phrased ultra-postmodernism, slurred neoliberalism or could it actually be an apolitical stance? Who makes weak monuments speak? Who in the world listens to them? What if weak monuments fail?

I assume that these are some of the issues the exhibition will raise. As there is still a long time to go until the vernissage (I am writing half a year before it), I had better not get into further details. As an alternative I will offer a personal reading of the (weak) monuments I have encountered. In the end I will try to draw attention to some of the “monumental weaknesses” inherent in the concept of weak monuments. This of course is not meant as criticism of the show I have not seen yet, but to provoke further discussion on this enchanting topic.

2

My kids, instead of asking me to read them children’s books before they fall asleep, demand that I tell them stories from my childhood. So far I must have recalled several hundred memories. For all these impressions, I am thankful to my parents who didn’t put me and my brother in kindergarten and let us hang around with our 90-something-year-old great-grandmother who by that time had lost nearly all of her sight and hearing. This is why we spent most of our early childhood hanging around the city and its outskirts. Likewise, I have only a few (positive) memories of school, but plenty of impressions of what we did after the school day was over. I have noticed that whenever I start to tell these stories I first have to dig deep into the places we visited. Memories lie in space. I think of a certain street and recall the events which took place there. I think of trams and take a trip down memory lane with the weird co-passengers we met. I am aware that there are people whose memories are dominated either by sounds, colors, tastes or seasons. In my case it is spatial relations. Mental monuments constitute who I am.

3

I tried to recall if I remembered any public monuments from my childhood. The only one I could think of which could have formed me as a citizen and turned me into a member of an imagined community was a sculpture of Hans Christian Andersen in Copenhagen. I was six years old when we first visited Denmark and I remember my mother telling me that if I sat on this figure’s lap life would bring me back to Copenhagen (it did). I can think of no other monuments being meaningful to pre-school me. At the same time all the rest of the city played a huge role in our upbringing: streets, courtyards, fences, garages, sheds, parks, fields and dumps. The more time we spent there, the more meaningful they became.

By the time I was more or less “fixed” as a human being, I had practically had nothing to do with public monuments. I am sure I am not the only one. What if none of us had any real association with monuments during our formative years? Why do we bother now? Indeed our lives now appear to be immersed in monuments, in strict national-cultural identities.

4

Most probably secondary school is when our lives pass from ineffective monuments to more vigorous monuments, starting with cultural role models. What can one say about the novels of the 1940s, the films of the 1960s, the music of the 1970s or the urban culture of the 1990s which attracted us so deeply back then? Whose monuments are these anyway?

5

Then came the student years. You try to make yourself heard in the public space. At first you get the impression it is ridiculously easy. In a way it really is, unless you are unhappy with the role of being a weak monument. And then what? Should you go monumental or stick to the grass-roots level? Slow food, slow cities, slow science and Slow Movement. Forgive me if the metaphor is too abrupt, but I see a certain link between weak/monumental space and members of society with/without voices. Is having a voice a choice? Is there a middle way, a common ground in between the loud and the quiet? Perhaps some of the slow ones don’t want to speak at all. Should we respect the silence of the slow monuments?

6

For me there is something unpleasant in the striving to animate, galvanize or even monetize anything or anyone. I am suspicious of a cultural agenda in which even the pavement is brought into the limelight and politicized. Even if I am conscious of the possibility of the urban space being inherently political, I need my pretense that in some parts it ain’t necessarily so.

7

As any lefty will tell you, it is very much so. Politics is taking over the commons slowly but surely. Karl Popper called it Utopian engineering. A method of ruling the state from the point of view that the society has a definite aim and one can consistently approach this goal using rational social engineering. In this sense even slow monuments stand for specific objectives. This will lead us to the silly question of how much the end can justify the means.

8

I ended up opposing monumentality and humbleness, the opposite of what the curators of Weak Monument wish to do. But it is very hard to go beyond binary oppositions when someone brings up weakness and monumentality. Still I believe that the curators will come out with a clever dialectical synthesis. Although I have argued that I am skeptical about the over-politicization of the ordinary, it nevertheless makes a lot of sense to inquire about the daily environment functioning as a monument. After all, the notion of hegemonic political narratives which I have emphasized here is only one (narrow) aspect of the monument. If we bring into play the incredibly wide spectrum of the (mal)functions of the monument, we can come up with remarkably rich metaphors. But if the oxymoron of the weak monument is working so well, how will you convince viewers that you are not at all interested in dissecting monuments? It takes a very good, exceptionally monumental exhibition to break down language. Hopefully Freespace, as a collective endeavor, will provide us with one..

Add a comment

Comments: 11